Cassie: Tell us about your childhood. Where did you grow up?

Gary: My standard answer to that is I never did grow up. Laughs. I’m an Army brat, so I grew up all over the place. I was born in El Paso, Texas, but that just happened to be where my parents were when I arrived. We lived in Japan for three years in the early sixties so my earliest real memories are from Japan. I actually kind of credit my early years there with a lot of my attitudes towards architecture. We traveled a lot. I really owe a lot to my parents. Other families would take vacations and leave the kids at the Army base. My parents took my brother and me with them on all of the trips. We would travel down through Japan and stay in small hotels and sleep on tatami floors. I have a lot of—they’re not specific memories—more like early images. I think I gravitate toward the Japanese sensibility that’s almost a modernism in a way. It’s a very simple, distilled aesthetic, but it’s all about using natural materials. I never really realized it until much later in my life that there was this sort of holdover from that part of my life.

Also, here’s an interesting little tidbit: the very first night I spent in Japan, we had flown to Tokyo and we spent at least one night at the Imperial Hotel which was a Frank Lloyd Wright hotel that was sadly demolished years ago. It was one of the few buildings that survived the Tokyo earthquake. I have these very vague sort of cave-like memories of this. After that, we crisscrossed the United States. We always ended up in Birmingham, Alabama, when my father was overseas. He spent a tour in Korea right after the war and in Vietnam toward the end of the war and every time he would go to a war zone we would end up in Birmingham because that’s where my mother’s family was from. We would come here and stay, either with or near her family. So he ended up retiring here and I was able to go to high school in Hoover. It’s like I had enough of traveling so when it was time for me to go to college and I wanted to be an architect, then Auburn was the choice because it was a couple of hours down the road and I was just tired of traveling. That’s how I ended up back in Birmingham after I got my degree. A lot of my friends were wanting to go to New York and get jobs with a big architect or go to Atlanta, and I was like, I just want to go home. I’ve been here ever since, out of sort of a fatigue of having a lifetime of traveling. I really wanted to put down roots and be somewhere. Now it’s been a ridiculous amount of time. Now I’m back to a point where I want to travel which is kind of a good thing. My wife likes that.

C: I was only in Japan for two weeks, but it remains one of the most special places I can imagine.

G: Hopefully I’ll get to go back and see. When you get to a certain point in age, it’s almost like you want to go back and remember things from your youth. Go on sentimental journeys.

C: I can imagine that as someone who has an inherent aptitude for design, that being in Japan would be really influential. Much of what they do is so intentional.

G: They don’t have a whole lot of room to work with so they have to make it count. It’s funny as I say that, maybe that’s another thing that resonates with me about doing beach houses.

Because beach houses are like that. Real estate is so precious and a house at the beach costs so much per square foot that I think one of my instincts is to be extremely frugal with space. Maybe that ties into the whole aesthetic and being in Japan.

C: It’s amazing the ways in which all of the strings unravel and then twirl back up.

G: Exactly.

C: Did you identify as a designer early? You said the Frank Lloyd Wright memory came back to you later. At what point did you think, okay, this is part of who I am?

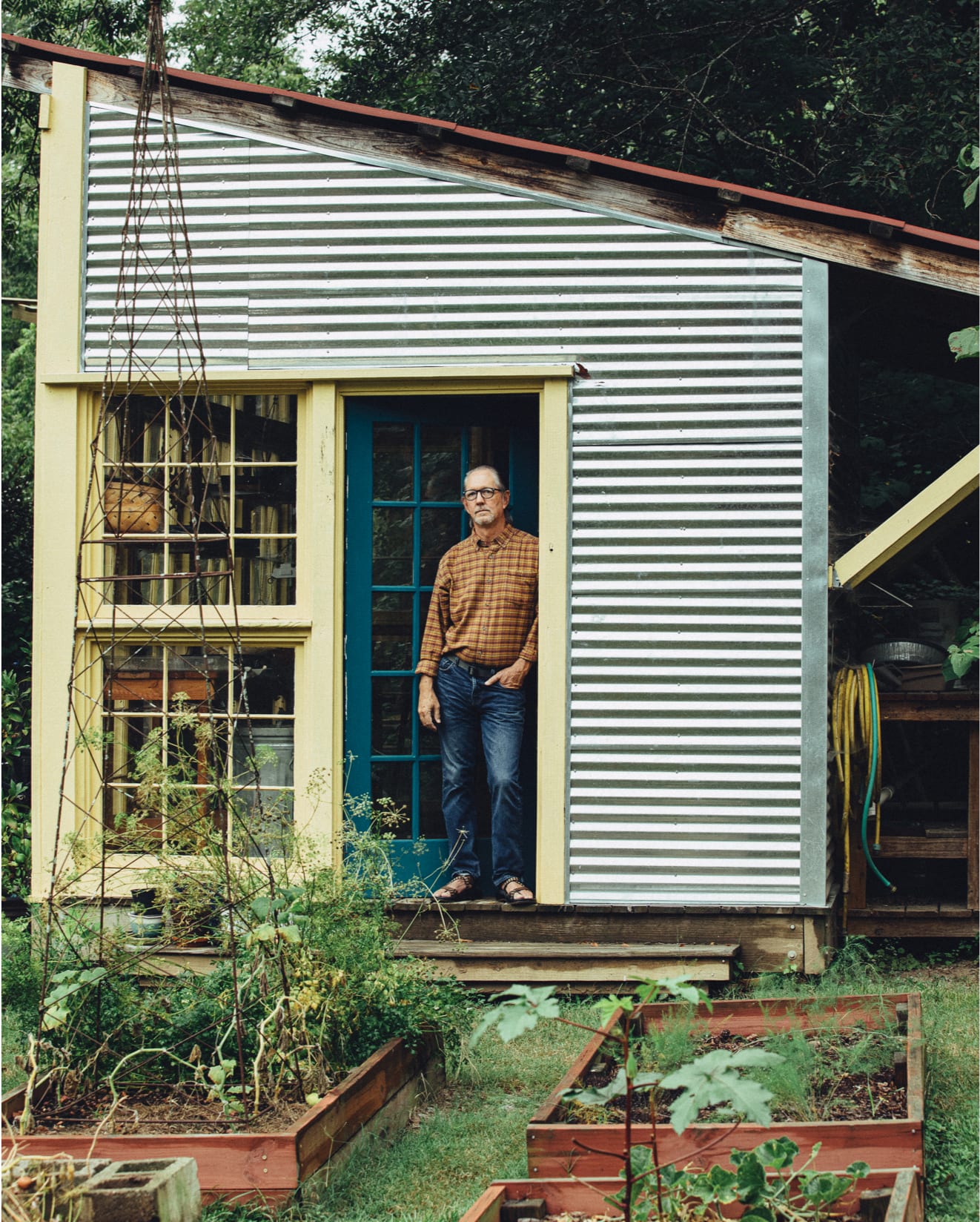

G: Honest answer? Fifth year in architecture school. I wish

I could say that I was a kid and I always wanted to be an architect but that would be a complete lie. The way this happened was I was sitting in a class, I guess it was my junior year in high school, and I get a call from the counselor’s office. They told me, “We’ve got a local architect in Homewood that likes to hire students to do drafting and you noted on one of your profiles that you enjoyed drafting.” I was mostly into art, but I had taken a mechanical drawing drafting class and I enjoyed it. So I thought, well, okay, that’d be cool. So I go work for this guy for minimum wage which at that time was $1.25 an hour. I think my check for the week was thirty bucks. He basically taught me how to draw a building in the very early stages back when people were all drawing by hand. He taught me how to run specs on a mimeograph machine. He worked out of his home, like I do. I’ve always worked on my own, never had an employee, and always at home. I think part of that too is the whole traveling around in the Army, you just kind of want to be home.

And so I took this job and I kind of enjoyed it. I didn’t have a passion for it but it was something I enjoyed doing and so when it came time to go to college I was like, I guess I’ll go into architecture, you know. And it’s almost like an arranged marriage. You hear about people who have an arranged marriage and then they learn to love their spouse. It’s sort of like that for me. I’ve sort of grown in my affection for architecture. And it sounds kind of sacrilege in a way that I don’t have this burning passion. But I think one thing that it does for me is that I’m really more into providing a service for a client. What really flips my switch is getting to know people. That’s one reason I think I’ve gravitated toward, largely, almost exclusively, custom residential. For fourteen years, my first fourteen, I worked for firms and did hospitals and schools and office buildings and university buildings. I fell into this beach house thing because a friend of mine in the early eighties bought one of the first lots at Seaside. I had gotten to know this couple through a local Bible study we went to, and they said, “Hey, would you design our house at Seaside?” Of course, I was thrilled. I did it as a moonlight project; I was designing hospitals during the day. I realized in working on their home that it’s more like tailoring a custom suit. There’s a specific person and you can take their measurements and you can find out what party they’re going to or what event they’re dressing up for, and you can do something that fits this person. So, that’s really kind of where I get the joy out of it. Yes, I want it to be a piece of art that I like, that I really love, but more importantly than that, I want it to be something that fits the specific person. And that’s really where I get my design inspiration.

C: A home is so personal, right, it’s not just a house, it has to house all of these things— people’s uses and functions and their space for rest and relaxation and where they feel safe, all of that—so how do you go about creating that for somebody? Do you get to know them in the process or is there an upfront thing that happens or both? It sounds like you’re a pretty organic type of person, like you just go with it, but I wonder if there is something prescriptive also?

G: Well, I am pretty intuitive and it depends on the client. The thing that I start with is listening. I try not to do much talking, at first. And I really try to encourage people to give me as much information as they can. A lot of people who are going to do a custom house, in most cases, it’s a kind of dream. They’ve wanted to do it for a long time, so often they will have a file, well back before Pinterest, they would have a file of magazine clippings and sketches and photographs. Often they’re kind of sheepish about telling me they’ve got these things because they don’t want to offend me or feel like they’re telling me what to do. I’m like, “It’s your house, you’re hiring me to design you a house so dump them on me.” And now with Pinterest lately everybody has just started a board. Which is kind of a blessing and a curse because now everything in the universe is out there but it’s also a place where I can post things and start a dialogue.

I’ll tell them, “If you want to do a sketch of the house you’ve always dreamed of, do it.” Because to me, it’s not telling me what to do. It’s telling me who you are. And it’s telling me how you’re going to use the house, what things are important to you. Why did you pick this specific lot? It can be just the feeling or it can be something really specific. The point is I just enjoy getting to know people and their specific motivations for doing this. It isn’t an easy process. You know, I think they say building a house is one of the most stressful things a couple can do. So they’re going into it for some really good reason or they’d just go buy something. I try to make it fun. I try to make sure I accomplish what their motivation was behind trying to do this.

C: Let’s talk about New Urbanism. What it means to

you. What it means to create a space that stands alone beautifully, by itself, but then also exists as part of a whole community.

G: So, the thing that really attracted me early to New Urbanism—really, two things: one was the traditional architecture and the other was the sense of community. Again, I’m more into this architecture thing for the people that I work for than for the building itself. And so the idea that New Urbanism was about a place that people would love, that people could learn how to be in a community with each other and be relatively free of the automobile, all of those things really resonated with me. And they still do.

C: I want to come back to Alys Beach but one more question about your work. Is it important that your work is interpreted in the way you intended for it to be or do you even have any kind of intention? It seems that you see it as a very personal process with the client, so perhaps it’s less about you, but I also know you take pride in your work. So what is the greatest compliment you could receive about your work?

G: I’ve never thought about that. I guess I just really don’t care much about what people other than my clients say about my work. It may be because for the most part my work is pretty humble. My homes don’t often end up in magazines and books because they tend to be a little more restrained. And I think probably, well, one of the biggest compliments that I do remember getting on a project— a beachfront home I did in Rosemary Beach actually— and I got compliments from both very traditional architecture friends and modernist architecture friends. And I was thinking well, okay, I’ve done it now, because it made both groups happy. It was a large house but it was one of the simplest houses I’ve ever done. It was basically just a big rectangle with really good proportions and good materials. I try to encourage people to, instead of spending money on really fancy jewelry, let’s do something that’s got good bones. And it’s going to be more timeless. I guess “timeless” would be my favorite adjective that somebody could put on one of my projects.

C: So, for you, there has to be some humility in timelessness. I mean, when you’re showing off, it doesn’t last.

G: Rarely. I do think that there are places for that. I was never a big fan of Frank Gehry, but my wife and I were in Bilbao once and I saw the museum and I thought okay, this really, really works. But I tell people, it’s like the way you’re dressed. You’ve got a really nice simple black dress but you’ve also got a gold pendant necklace. What if your whole dress was gold, you know, sequins? Your gold pendant would be lost. There needs to be humility. There needs to be a black dress for the jewelry to shine. Frank Gehry is like the jeweler. But you wouldn’t want a whole city of those; it would be a disaster. I tend to do the black dresses.

C: And probably the satisfaction for you too, beyond being in some book or magazine, is in having the people who call these places home feel that they are indeed home.

G: Right. I really love it. For the most part it seems that my houses have stayed in the family. It’s like, if somebody loves something enough, they’ll hold onto it and pass it down. I used to use the analogy— did you ever read the children’s book the Velveteen Rabbit?

C: Of course.

G: You know, something that’s loved enough and beaten up enough and used to the point to where it has a soul. To me, that’s the way I want the houses to be. I want a house to be able to stand up to abuse but still have its spirit. And then it becomes something that you want your kids to live in or vacation in, however you want to use it. I want it to have some meaning.

C: Well, and having good bones is definitely the most essential part of that being able to happen.

G: Yes, because a house can always be renovated or updated, but you can’t really renovate the bone structure. You can change the color of the tile or switch out cabinets, but it’s really hard to make major—it can be done—but it’s hard to make major, major changes. Might as well just take it down and start over.

C: You’re giving me lots of things to think about. Back to Alys. You were involved early, the earliest. Can you tell me, you’ve touched on it, but can you tell me a bit about the earliest design philosophy. What were you tasked with, what were you trying to do together?

G: I was actually involved in the very beginning planning charrette that DPZ [now DPZ Codesign] did to lay out the lots. The way they structure these charrettes is that they’re ninety percent about urban planning but they’ll often have an architect or two in the room to start exploring the architectural style. They’ll develop a town center and basically start exploring the character of the architecture. I pitched an idea to come in as a separate consultant at the charrette to start doing concepts for plans. I knew enough about the plans to know that what they were going to do had never been done before.

The idea of hybridizing Bermudan architecture DNA with Antiguan patio house types— it’s like a weird marriage. So I said, “What if I just sit at a desk over in the corner and when they start laying out lots and beginning their design code, I’ll just spit out concepts that’ll help us understand—what can you get on a 40 by 80 foot lot that’s a courtyard house with a Bermudan exterior? What in the heck is that?” About six or eight months later they organized a true design charrette for houses. Because I had been invited that early I was invited to be one of the seven or eight architects there. We all flew into South Beach, Miami, and holed up in an Art Deco hotel and sat in the ballroom. We each designed two houses in those five days and had a blast doing it. I love charrettes because there’s all this interaction. It was funny because even then I was saying that I’ve been studying these Antiguan towns and courtyard types and the exterior facades on these houses are basically not designed. They’re just random; there’ll be a random grouping of windows on a flat wall but it’ll have a really cool gate. So I was trying, even then I was trying to tell everybody, look, the outsides don’t matter so much, it’s about the courtyard and everybody was coming up with these cool pieces of architecture, of course, and I’m over here going let’s simplify. Someone said, “Don’t pay Gary as much, he’s not trying as hard.” Laughs. I said, “I’m the palate cleanser. You guys do the rich desserts and I’ll do the sorbet.” It was fun. We ended up with the sixteen houses and I was really blessed that one of mine was picked to be the first model home.

C: Pretty cool. Also great that you use the word blessed to have the first model home when I’m sure it was really just a huge testament to your work.

G: It could have been any of us. Let’s just say it—I’m just a good old Alabama, Birmingham, home boy. I don’t have coffee table books. So when I get an opportunity like that, I really consider it a blessing. It would have made more sense, PR-wise, to go with somebody who had more of a presence out in the world than I did.

C: You’ve done it on your own which is admirable. What about how Alys has changed over time? Is there anything striking in terms of how the design philosophy has evolved or how it’s moving forward? It sounds like you’re still involved.

G: There are two things. One is just sort of the way of things, but, design-wise, it’s gotten much more elaborate; the volume has been turned way up. That’s happened on every project on 30A. The one thing that I’ve noticed that tends to happen and I think it happens more in a higher-end resort market like 30A, because it attracts people that are really design connoisseurs, is that everybody seems to want to out-design everybody else. And so there is this curve where things start out fairly simple and then they get fancier, fancier and fancier, more elaborate, more expensive.

I try to be a counterbalance by encouraging people to have the courage to be simpler and more humble. I try to get people to be restrained on the exterior as much as possible because to me that makes a better community; a better street is really made up of a series of more humble houses. Because if every house is trying to jump around and say, “Hey, look at me,” then it really gets kind of chaotic. Right now I’m doing a series of houses for the Somerset Program (a side note, but in that original charrette, Somerset was the original name for Alys) that are under construction right now that I call Mykonos houses. I encouraged them to use that model, the Mykonos and Santorini Island houses, because they’re basically just stucco boxes. They have some rounded corners, they’re really sensual, they’re really beautiful, but they’re ultra simple. I was telling them, the folks at the sales office, “Not only will this be a little less expensive to build but it will give people permission to calm down.” This circles around to my early days in Japan after I thought about it because these houses are really more about the interior and the courtyards than they are about the outside.

The outside is very humble, but you go into the courtyard, and it’s like, that’s where everything happens. I remember when I was a kid and we used to visit the village to go have a bowl of ramen, often the streets were kind of dirty. It snowed there a lot and when the snow melted it was slushy and it was a typical village where everything goes on in the street and then you go through the doors and you take your shoes off. It’s a different world. It’s clean, organized, there are gardens, it’s like a little jewel box. That’s part of the differentiation in Alys, other than the white, the fact that these courtyards are like little secret worlds.

The other thing that’s really changed is there’s a lot more diversity in design style in Alys. Initially the architectural DNA was straight Bermudan. There’s been a lot of hybridizing coming in. I’m doing it too. The reason it works is because everything is white. So it ties it together. When you have a community of that size, it’s hard to hold it to one thing. I’ve started trying to circle back to the early days and do a little more Alys Beach classic. One of the houses I get the most compliments on I did for a Birmingham family, across the street from the rental office, and it’s a very straightforward Bermudan home type.

Those are the two big things: the variety of influences and the complexity. It’s done really, really well as far as the urbanism goes. It’s still holding close to the original concepts. There’s some tweaking to meet market influences, lot sizes get adjusted, but that’s just part of the process.

C: It seems like Marieanne Khoury-Vogt and Erik Vogt, the town architects, have been instrumental in keeping that in place.

G: Oh, gosh yes. They’re the common thread. They’ve been here from day one. The place would not nearly be what it is without them.

C: Do you ever go there for vacation?

G: I try to. When I get down there, of course, I always try to combine the trip with at least a day of a job site visit. I’ve been going to 30A every month for twenty-six years. I live in Birmingham because this is where family is and where my home is, where my kids grew up, and now I’m having grandkids so we ain’t going nowhere, but I’ve gone there literally every month. I think I skipped one because of COVID and maybe there was one other time. In fact, next week we’re renting a house, going down and taking the family. I’m going to try my best to only do one day of business and actually have a vacation—socially distant vacationing.

C: So nice. Is there anything else to say about Alys, anything that particularly draws you to go back, anything you especially love?

G: It’s almost like picking a favorite child. You love them all.

C: Yes, but you do have a favorite. I tell my parents that all the time, I know you have a favorite so you might as well quit denying it.

G: Laughs. I think one thing that’s really great about Alys is that everybody who spends the money to buy a lot and build there is doing it because they really value design. What I really love about designing beach houses, generally, and lake houses too, resort, getaway type places, is that people are in the mood to do something fun. They don’t want to build the house that they have at home. People are very game to do interesting things, whimsical things. They think outside the box. That’s one thing I really love about Alys; virtually everyone I’ve worked with there is game to do something fun and high quality. And I do love the all-white; it’s almost more clean and modern by default. It’s just a really beautiful kind of sandcastle of a place.

C: Often the exploration of other creative outlets helps to grow and focus our creative gifts. I always say creativity begets creativity. How do you continue to grow yourself creatively?

G: You see that wall? (Points to a wall full of guitars) I’m a musician mostly. As much as I’m an architect, I’m a musician. When I was in high school, I taught myself how to play keyboards and faked my way through a band. At Auburn, I overheard a couple of guys a year older than me talking about starting a band and needing a bass player. I lied and said I played bass. I promptly learned. They didn’t realize that I had lied to them until our fortieth anniversary reunion. I said, “You know, guys, I never even owned a bass. I went home that next month for Christmas and told my parents that’s what I wanted for Christmas.”

I’ve always really loved music whether I was faking my way through Bach or learning the bass line for Stairway to Heaven. I honestly have to say that’s probably my first love. I’ve been playing almost continuously every day since high school. I just dedicated myself to bass because that was an opportunity but again that’s my personality. When I look back on it, I see that it fits me perfectly because I’m not really calling attention to myself. But I’m supporting a group, you know, supporting other people. Underpinning what they’re doing. Rarely does the attention end up going to the bass player. But the bass guitar is sort of like the rudder under a ship— you may not see it but it’s determining where everything is going. It’s a passive- aggressive kind of instrument. Laughs.

C: Do you listen to music when you design? What artists, what types of music do you listen to?

G: Sometimes. I listen to rock and roll.

C: Who are your favorites?

G: It’s funny. I have pretty eclectic tastes. There’s a lot of classic rock that I grew up with that I listen to— the Beatles, Led Zeppelin. I was really into Yes. Lately I’ve gotten more and more into songwriters. My current favorite songwriter is Jason Isbell. Seen him numerous times. That’s been my main hobby for the last five years: I’ve started songwriting. Largely because when you get to my age, you start hearing yourself say things and you go, wait a minute— like you say, I can’t write a song and then you go, wait a minute, I never tried. I’m gonna try. Maybe I can’t. But maybe I can. So I just started and, fortunately I go to a church with a very contemporary music program and I’m the bass player in the band. It’s a very creative atmosphere. Anybody can bring a song and we’ll see if it’s good. We’ll play it and see what happens. Just like anything you do, it starts off spotty and it gets better. I like to think I’ve gotten a lot better but it’s such a fun, creative outlet. That’s why I love Jason Isbell—he’s an amazing songwriter. And guitar player. And his wife, Amanda Shires.

C: My husband introduced me to them years ago, and we’ve since seen them probably a dozen times. His songs can stop you in your tracks. They can just about make you weep.

G: I’ll have to admit that every time we see him live and he does that song Cover Me Up, I’ll tear up. I love that, and lately I’ve become a latter-day Dead Head. When John Mayer joined the new version of the Grateful Dead with Oteil Burbridge, the bass player out of Birmingham who came on after the Allman Brothers retired, I told my wife, “Let’s go to New York and see how this is.” I’d been following John— I first saw him at a street festival in Birmingham, just him and an acoustic guitar and maybe five people in the audience. And it took maybe two songs, and I was addicted. We’ve been to over twenty shows, including six on the beach in Cancun. We had five shows booked for this tour that just got canceled because of COVID-19. It’s like this whole repertoire of music that I didn’t really know so it’s been fun to go back and pick up on the whole thing all the hippies were following. It’s the ultimate people watching, going to a Dead show. Very interesting subculture.

C: How do you begin your day? Do you have any type of daily ritual?

G: Coffee with my wife. Since my daily commute is literally three seconds across from the master bedroom to the office, that’s probably about it. I used to read but I bought an iPad and now I play solitaire on my iPad and drink coffee. Not very profound but it’s what I do to get started.

C: When you’re not working, where are you? Sounds like you’re home…

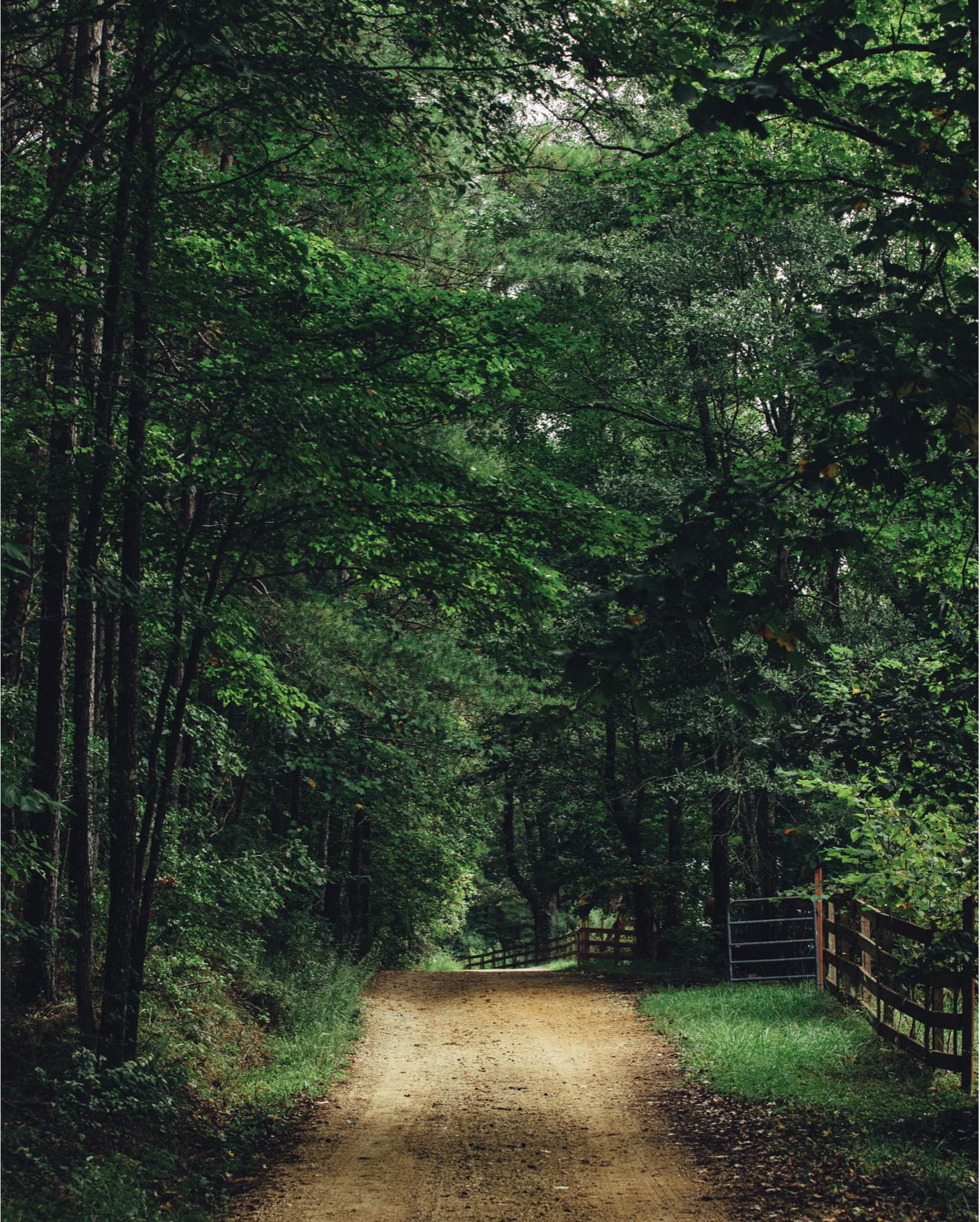

G: We live out on 350 acres of family property. My wife’s grandfather bought this land about sixty years ago just south of Birmingham. I go for walks down the road. I’ve got an acoustic guitar that I write songs on and when I need a break from drawing, I’ll pull it down and play something. I mow the grass. This morning, my morning ritual, and this only happens a couple of times a year, I went out and helped my wife get all the bachelor chickens, the roosters, and put them in a dog crate and take them to the processor. Because much like male humans, male chickens aren’t worth much. Laughs. They just make trouble, babies and trouble. We usually keep one or two roosters around to protect our hens but other than that… She pulled all the chickens out and I just had to shut the door behind each chicken. Then I came up and had a cup of coffee and started working.

C: You don’t have an employee. So, you do all of your scheduling, your marketing, your social media?

G: Whatever there is, I did. I have no employees, no consultants. My wife does my books. I call her my normal person consultant. I often call her in to do design critiques because she’s very perceptive (dear, that kitchen will not work). She’s as close to an employee as I have and she isn’t. She’s my partner. So, no, I don’t have a social media person. If it ends up on Instagram it’s because I did it.

C: You’ve mentioned church. Do you have an active spiritual life?

G: I’ve been a believer since I was a little boy. I remember going to I guess the base church, there was a missionary couple. It’s one of those things where you’re a little kid and you hear the Gospel and it’s very true and simple and straightforward. We all know there’s no such thing as a good person but you make a choice of whether you’re going to try to live right or try to live wrong. I remember as a small child making that decision. Of course as you age you go through phases of understanding and doubts and you realize that some things you thought mattered, don’t matter; some things you thought didn’t, do. It’s always a matter of learning in the path.

That’s the most important thing. And I think that’s one reason I look at architecture more in the realm of service to a client.There is a concept of spiritual gifts and you’re commanded to walk in all of those gifts, but there are one or two that are sort of the bias of your cloth. Mine has always been service. I’d rather go put up chairs in the auditorium than go speak. I would rather do something practical and helpful. So yes, I’m a Christian and it’s the biggest part of my life.

C: I was hoping to draw that out because it does line up with the way you talk about your work and all the things that you do and that you value.

G: One of the few fundamental Christian Dead Heads in existence probably. Fortunately my wife is also.

C: Ha, no doubt. I can’t thank you enough. It was fun and interesting and I appreciate your honesty and openness, being willing to talk and share.